David Schlegel, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

October 13, 2021

DESI has broken its own records, mapping the three-dimensional location of 100,000 distant galaxies and quasars in the single night of October 8, 2021.

The DESI Main Survey started on the evening of May 14, 2021. Nearly 100 scientists joined the operations team on Zoom that night to witness the beginning of the survey. It wasn’t a perfect night, as the “seeing” (blurring of the sky from atmospheric turbulence) was worse than typical, and some time was lost to instrument communication errors. Even still, eight dark-time tiles and ten bright-time tiles were observed, which was enough to set a record (for any telescope) of mapping 60,000 galaxies in a single night.

The operational efficiency of DESI has been improved since that first night. One important aspect of this is the “robustness” of the complex instrument and control systems. There are 5000 fiber robots on the top end of the telescope commanded to move every 15 minutes, 6 guide cameras, 4 optical wavefront sensors, 30 cryogenic cameras taking data in the spectrograph room, a large assortment of sensors, and dozens of computers to control all these systems. It’s not uncommon to have minor, non-critical faults somewhere in the system, and those faults have to be trapped rather than bring the whole system to a halt.

Operational efficiency also relies upon a careful choreography of reconfiguring the instrument between observations: the telescope is slewed to its next sky location, the focal plane is re-focused as the 375 tons of moving weight slightly sags under gravity, the 5000 fiber robots are re-positioned to point to the locations of unobserved galaxies, and the previous spectroscopic exposure is read out. The inter-exposure time for this dance of activities that was typically 3 minutes during the first night of the survey has been reduced to 2 min 15 sec. For this particular record-setting night, the open-shutter efficiency was 87%, meaning that’s the fraction of time that the shutters on the spectrographs were open and integrating on light from distant galaxies.

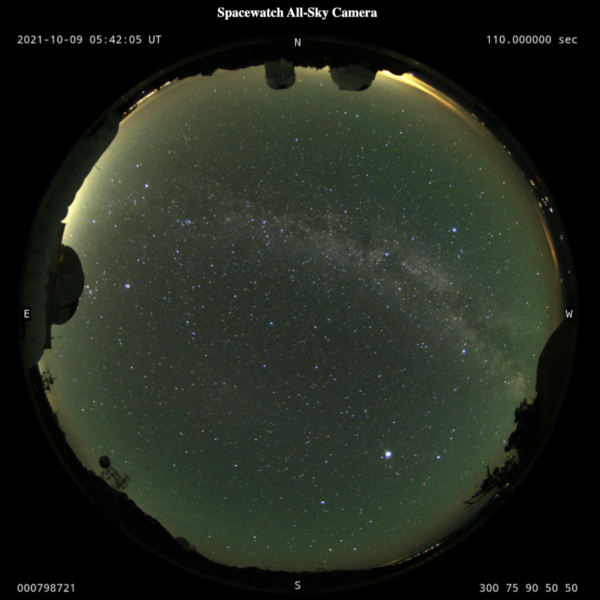

Finally, the weather needs to cooperate! The night of October 8th was a fully “dark” night, meaning that the moon was below the horizon. The skies were clear (“photometric”) for all but a few minutes when a thin cloud layer blew through. And the “seeing” was excellent, such that the blurring of the atmosphere was less than 1 arcsecond for most of the night. The sky wasn’t quite as dark as the best nights, partly because we were observing near the ecliptic plane where dust particles in the solar system reflect small amounts of light from the sun. In combination, the weather was sufficiently good that we were running at a survey speed of 120%—meaning 20% faster than expected under nominal, good conditions.

How many galaxies were mapped in this one night? We completed observations on 29 dark-time tiles (with one tile completing observations from a previous night). Each of those tiles included approximately 4200 high-redshift targets (galaxies or quasars), with the remaining 800 fibers assigned to calibration targets. Most of those galaxies were “redshifted” (mapped) in a single observation. These data were analyzed by 10 am the following morning on NERSC (the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center) to confirm reliable redshifts for 98,954 galaxies and quasars. Additionally, two bright-time tiles observed during evening twilight measured redshifts for 4225 low-redshift galaxies, bringing the total haul to 103,179 galaxies and quasars.

Will this record be broken in the future? Most assuredly, if only because the nights are getting longer. This record-setting night had 9 hours 22 min of time between astronomical twilight (when the sky is darkest with the sun at least 18 degrees below the horizon). The best nights for setting records will be the new moons closest to the winter solstice. This year, that will be the nights of December 3 (10 hours, 57 minutes) and January 1, 2022 (10 hours, 59 minutes).

Congratulations to the observing team for the night of October 8, 2021: Liz Buckley-Geer (Fermilab, Lead Observer), Abby Bault (University of California Irvine, Support Observer), Mike Wang (University of Edinburgh, Support Observer) and Thaxton Smith (NOIRLab, Observing Assistant).