Joan Najita (NOIRLab)

10 March 2025

“Perhaps only in a world of the blind will things be what they truly are.” — José Saramago, Blindness

We’re all human. Science is a human endeavor, carried out by humans with all their imagination, creativity…and biases. Sometimes we explore the Universe without expectations, but often we have an idea of what we may find (a hypothesis, a hunch). These ideas motivate and guide us in our exploration. But they can also introduce confirmation bias, “the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting information that is consistent with…existing beliefs.” (Britannica). In its quest to make precision cosmological measurements, DESI uses a process called “blinding” in its analysis methodology in order to avoid the inaccuracies that can arise from confirmation bias.

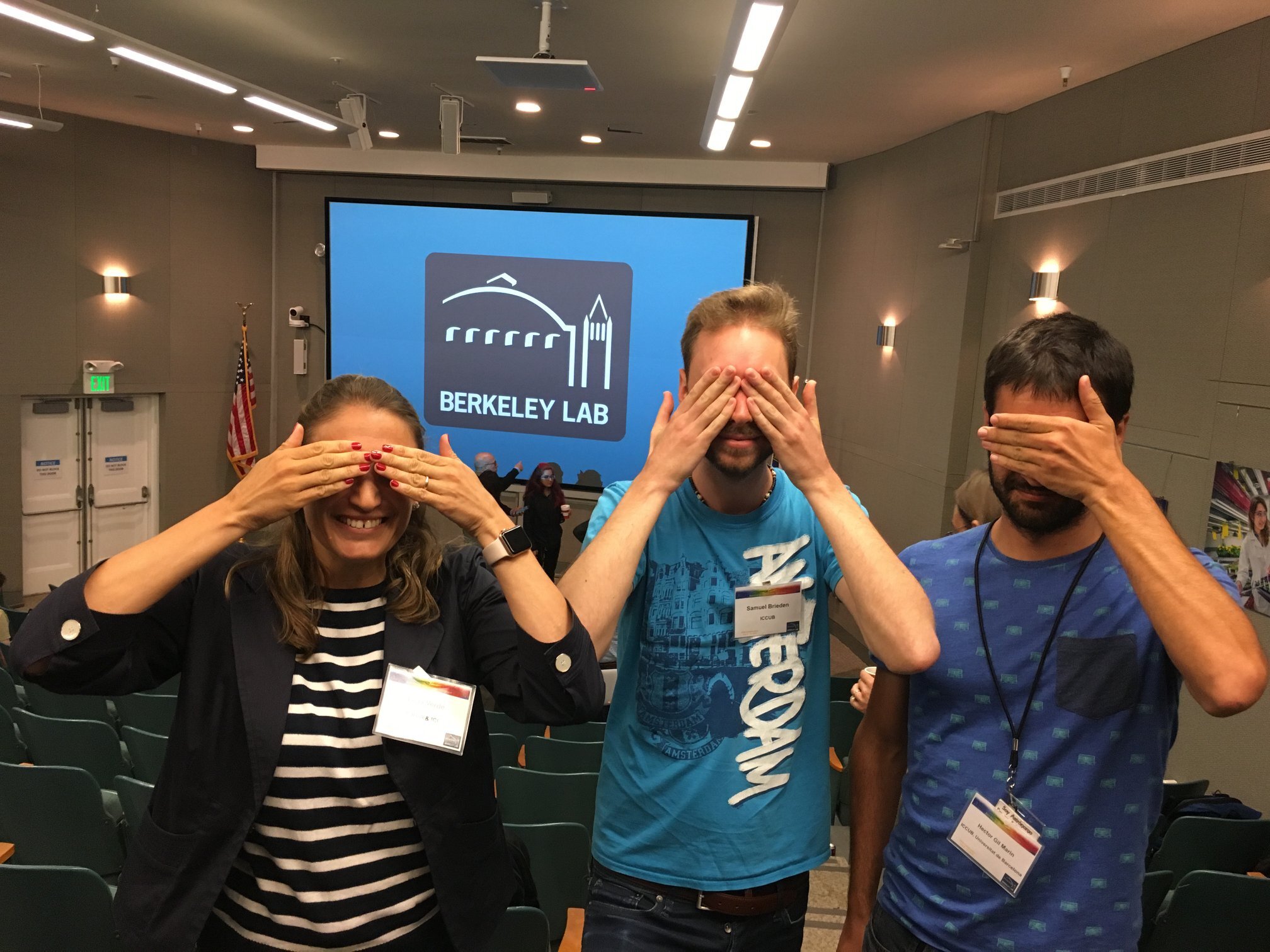

We sat down with DESI scientists Sam Brieden (U. Edinburgh), Uendert Andrade (U. Michigan), and Juan Mena-Fernández (LPSC, Grenoble) to learn about how blinding works, the rationale behind it, and what it’s like to work this way.

Q: What is the general purpose of blinding in research?

Sam: Research is never carried out in a vacuum, it is always bound to existing knowledge and expectations. Every researcher or group of researchers is subject to external influences that may affect the way an analysis is performed. For example, a new analysis result that is in agreement with current consensus and does not contradict any prior results, is more likely to be accepted by the community. On the other hand, if a new result is unexpected, it is more likely to raise eyebrows. Due to this “pressure”, researchers unconsciously tend to examine unexpected results more closely and, say, include more cross-checks and caveats, or a less optimistic error estimation. In other words, there is a trend in research that expected results tend to be treated with less scrutiny than required, while unexpected results may be tweaked until they agree better with expectations. In “The Neglect of Experiment,” Allan Franklin describes the process this way:

“Although each experiment was honestly made, they were, except for the first, conducted in light of previous results. In any experiment, the sources of error, particularly systematic error, may be hidden and subtle. This is particularly true of…technically difficult experiments. The question of when to stop the search for sources of error is then very important. One psychologically plausible end point is when the result ‘seems’ right.”

This phenomenon can lead to a so-called “confirmation bias”, the trend that research results are likely to align with previous results, even though they might be wrong. Carrying out a blinded analysis, where the actual research results are “hidden” from the researcher until all the analysis choices have been made, is an effective way to shield oneself from that sort of bias.

Therefore, more and more natural science branches routinely adopt blinding strategies to reduce confirmation bias in an optimal way.

Q: What is special about the way DESI incorporates blinding in its analysis methodology?

Uendert: DESI employs a unique blinding strategy that is intricately designed to mitigate experimenter bias while ensuring the integrity of the analysis. In broad strokes, there are three steps: (1) We first create data that’s plausible but shifted away from the truth. (2) We then refine our analysis method by working with this ‘’test’’ data. (3) When we’re done, we apply the analysis method to the real data — in a step called “unblinding”, i.e., the “big reveal” — and no further changes are allowed.

Thus, we are masking the truth at the data level. In the first step, creating the test data, we start with the real data and shift galaxy positions along the line-of-sight to mimic a different, randomly selected cosmological model, thus preserving the statistical properties of the data. Such a comprehensive approach is tailored therefore to DESI’s specific observables (baryon acoustic oscillations and redshift-space distortions) and represents a significant step forward in the practice of blinding in cosmology, especially in the context of large spectroscopic surveys.

Q: What is it like to do the analysis “blind”? (is it disorienting? liberating? or pretty much like normal research?)

Juan: I must say blinding felt a bit weird to me at the beginning of my PhD. Depending on the methodology adopted for blinding, you might not be allowed to see the data at all. And sometimes, you might be allowed to measure things on the data, but not to look at the results (which you might really want to look at!). However, after several years working in large collaborations, now it feels like a part of the process of doing science.

Uendert: Working with blinded data can feel both liberating and challenging. On the one hand, it frees researchers from preconceived notions about the results, encouraging a more objective and unbiased analysis. On the other hand, it requires a strong trust in the analysis pipeline and the blinding process itself, for which we have to creatively design tests and then carry them out. The anticipation of discovering the true cosmological parameters after unblinding adds an exciting layer of mystery to the research.

Q: What is it like to experience the “unblinding”? Is it exciting? What emotions do you have?

Juan: I have experienced several unblindings, and these are always extremely exciting. The unblinding is typically done in a video call meeting in which everyone in the collaboration can connect, and so there are a lot of people watching. This usually makes me feel nervous, especially if I’m deeply involved in the analysis (partly because the analysis could have taken months or even a year to carry out). There are lots of things to prepare for an unblinding, such as slides to present the project and scripts that will create the unblinded plots and output the results. The most exciting part is that moment in which you press the button to run your script and obtain the final unblinded measurement!

Uendert: For me, as you might imagine, the moment of unblinding is filled with a mix of excitement, anticipation, and a bit of nervousness. It’s the culmination of years of hard work, and there’s a tangible sense of revealing the Universe’s secrets. The experience is akin to opening a highly anticipated gift; you’re eager to see what’s inside but also hoping it meets your expectations. Regardless of the outcome, it’s a pivotal moment that deepens our understanding of the cosmos.

Sam: I was really excited in anticipation of the internal full-shape unblinding event on 12 June 2024 — which revealed the results that were eventually published on 19 November 2024 — since I developed both the Blinding and the full-shape (i.e., ShapeFit) methodologies during my PhD. Coincidentally, my wife and I were expecting a child, and we went to hospital on the same day, so I missed the DESI unblinding in favor of another (and for me personally even more exciting) unblinding event!

Q: What aspect of the DESI results are you looking forward to next?

Juan: I’m always looking forward to seeing the constraints in cosmological parameters inferred from the data, in DESI or in any other experiment.

Uendert: I’m particularly looking forward to seeing how the DESI results will refine our understanding of the dark energy equation of state and its potential evolution over cosmic time. The scale and precision of DESI’s dataset offer an unprecedented opportunity to probe the dynamics of the Universe’s expansion and the nature of dark energy. This could lead to groundbreaking insights into one of the most profound mysteries in cosmology.