by Alma González (University of Guanajuato, Mexico) and Martine Lokken (Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain)

24 April 2025

DESI’s educational program for high school students, DESI High, is now back in session!

Designed so students can work with DESI data directly from the telescope, the program also introduces fundamental concepts in cosmology and helps develop computer programming skills. The program was a huge hit with students in online events held during the pandemic and for a couple of years thereafter. However, it has been a while since we offered an event, especially in person.

But now DESI High is coming back in full swing. We are re-factoring and improving our Jupyter notebooks, testing new platforms to host them, and more importantly, we are adding examples that illustrate how to access the now publicly-available DESI data and new notebooks. Beyond that, we are aiming to offer new tutorial sessions on how to use such materials, both in-person and online. In February, we hosted the first two events of 2025, in Cozumel, Mexico and Catalonia, Spain.

Our first event, held on February 8th, was co-organized with the Cozumel Planetarium, CHA’AN KA’AN, who invited us to commemorate the International Day of Women and Girls in Science (February 11th). Of the approximately 20 participants who joined us on the day of the event, many were female students from the Quintana Roo area, which is located in the southern part of Mexico. Over a two-hour hybrid session, the participants interacted with DESI members, including Andrea Múñoz from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM, Phd Student), Diego González from University of Guanajuato (UG, Msc student), Maria Pineda (UNAM, undergraduate student), John Suarez from Monterrey Institute of Technology in Guadalajara (researcher), Fanny Rodríguez (UNAM, MsC student), a non-DESI undergraduate student Daisy Torres (UG) and Alma Gonzalez (UG, researcher). Mariana Vargas (UNAM, researcher), also a DESI member, participated as well in preparations for the event.

The session began with an introduction to DESI science as well as time for the students to get to know the instructors’ motivations to get into science and what their daily life is like working in DESI. Then, the instructors and students delved into the DESI High notebooks in Spanish! For this session, we partnered with Camber Cloud, a first-of-its-kind scientific and research cloud computing platform that provides low/no-code “science engines” for researchers to run simulations, analyze large data sets, and train AI models. They kindly provided test accounts for our students so that they could experience the entire process of making a copy of the DESI High repository, running the notebooks, and saving their progress. While we also offer other platforms to just plug-and-play, this gave students the opportunity to see the entire process from start to finish, which all worth it. We are expecting to have a follow up session with this team.

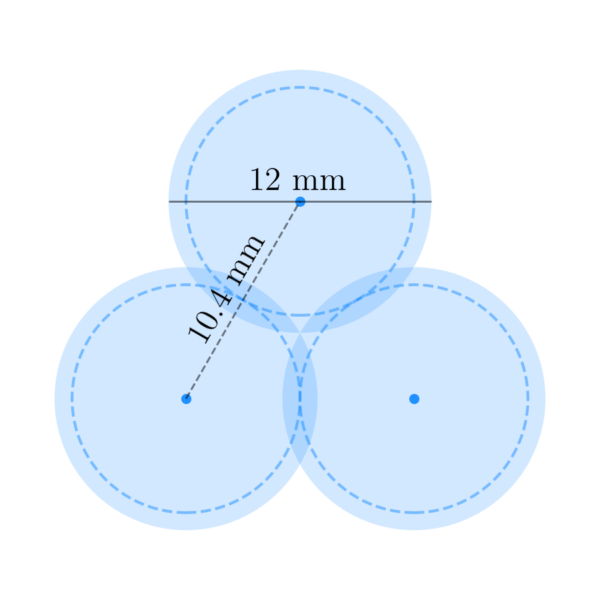

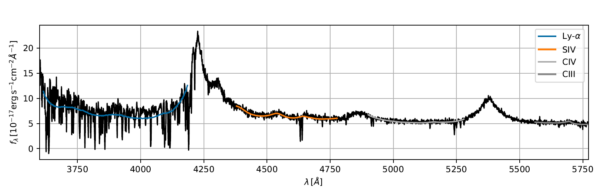

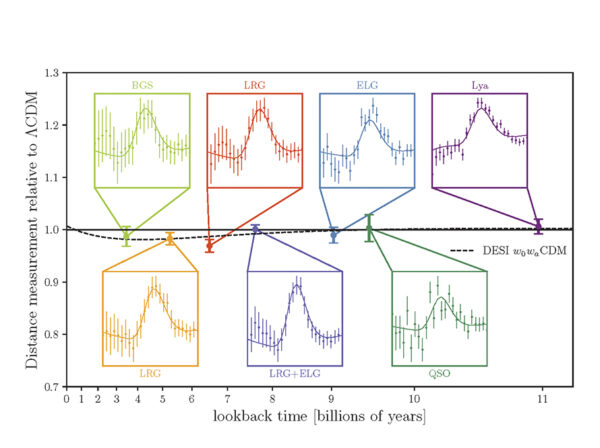

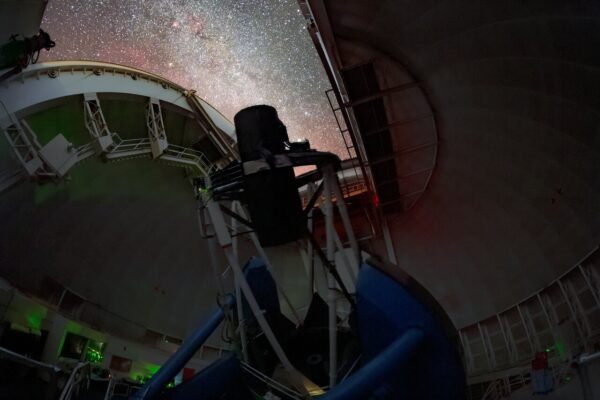

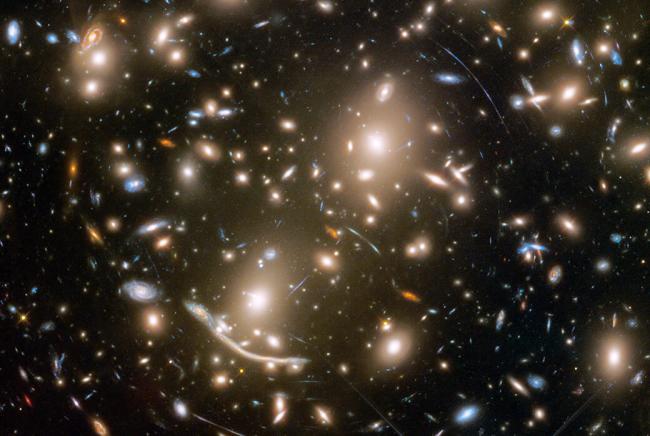

At the second event, on Feb 22, approximately thirty high school students from across the province of Catalonia, Spain, joined us at the Autonomous University of Barcelona campus to learn how DESI is measuring our universe’s expansion. For the cosmology edition of the “Bojos per la Física” (“crazy for physics”) annual program, three cosmologists from the Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE) led the students through the introductory DESI High tutorial notebook. This notebook uses Python code to demonstrate how measuring the spectra of distant galaxies translates into understanding the universe’s contents. The students also got an overview of how the DESI telescope works, and examined a prototype of the Guide-Focus-Acquisition (GFA) cameras that IFAE engineers developed to help guide the DESI robotic fiber array.

The day’s activities were run by DESI members Laura Casas (Phd student) and Martine Lokken (Postdoc), and Dane Cross (PhD student in the DES collaboration), who also shared what their day-to-day research life is like. Many of the students are interested in pursuing physics in the future, some in astrophysics and cosmology, and this program helped them understand the current research landscape as well as a typical day in the life of a cosmologist.

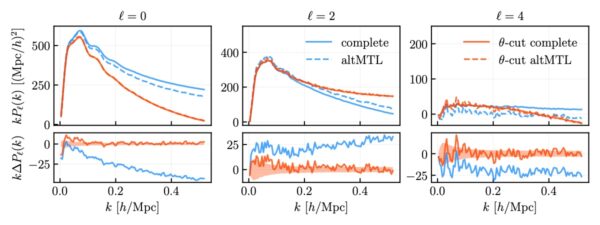

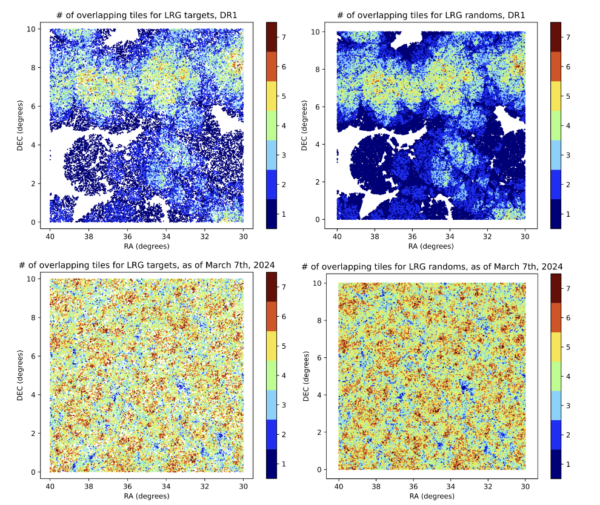

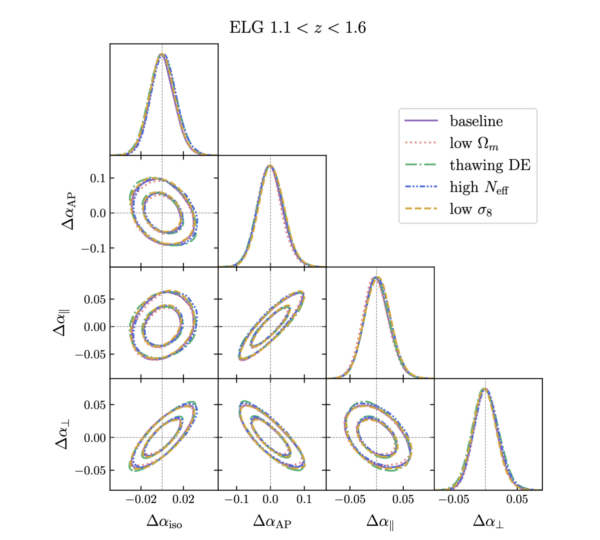

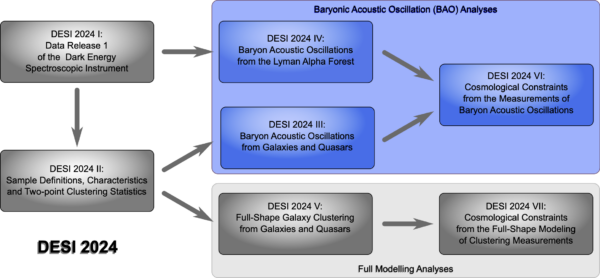

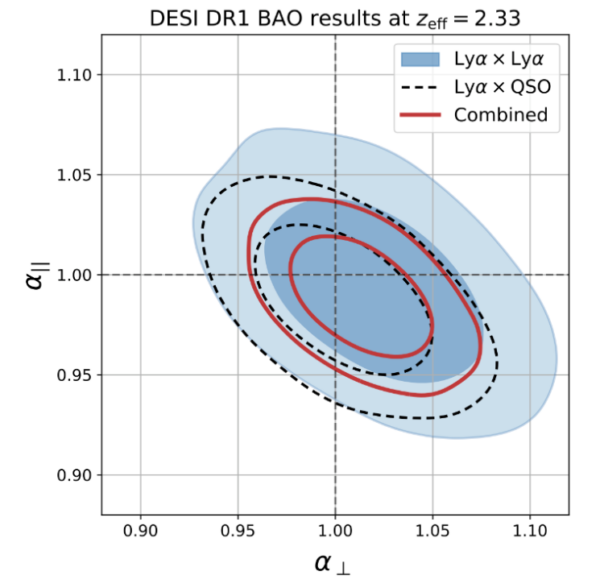

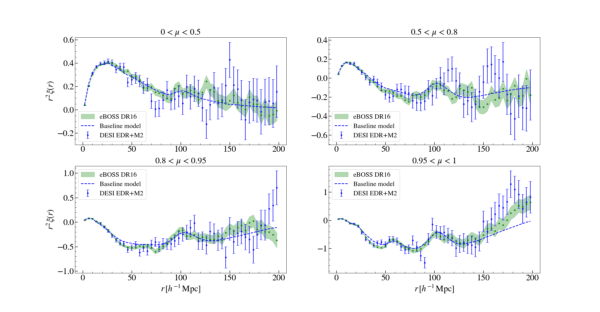

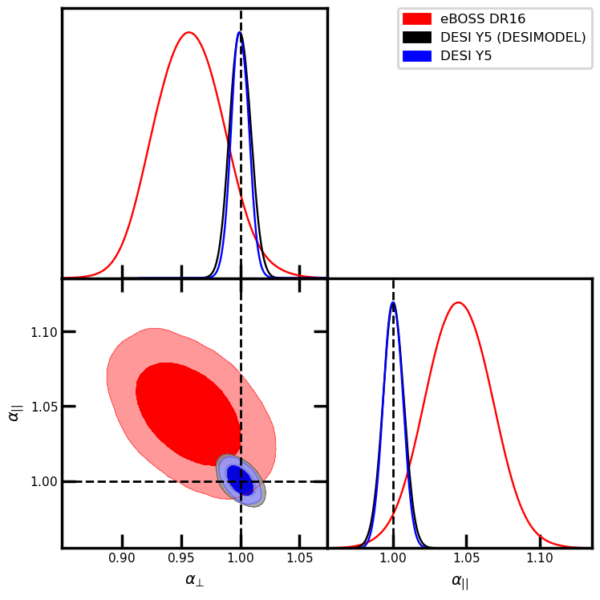

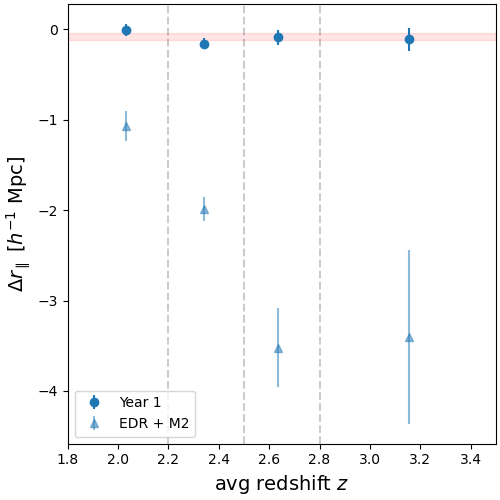

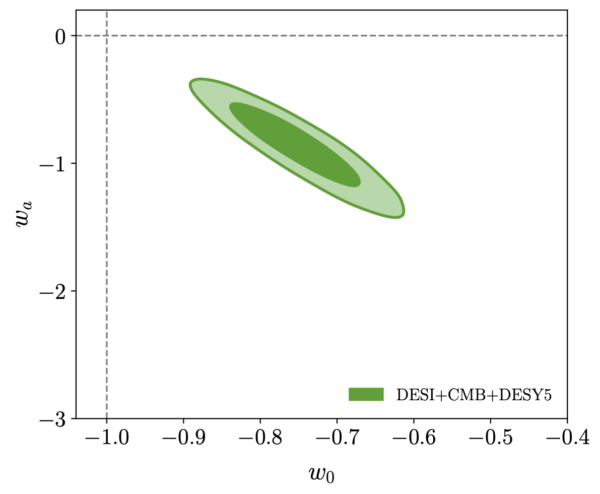

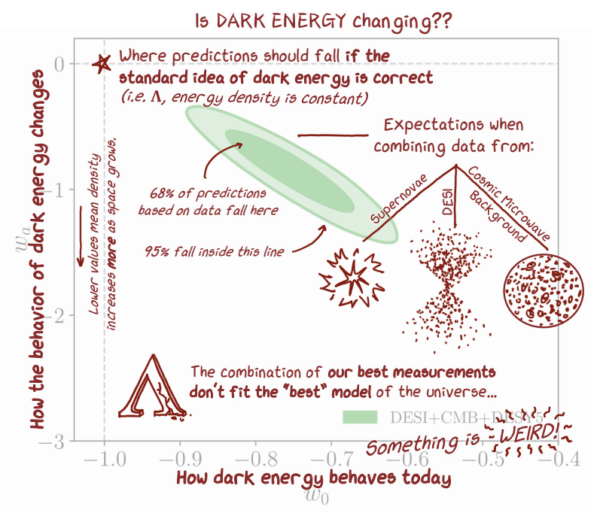

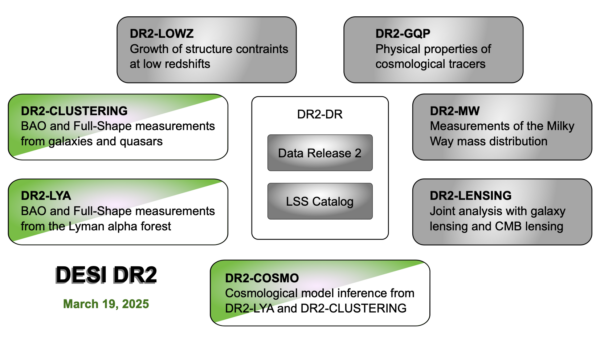

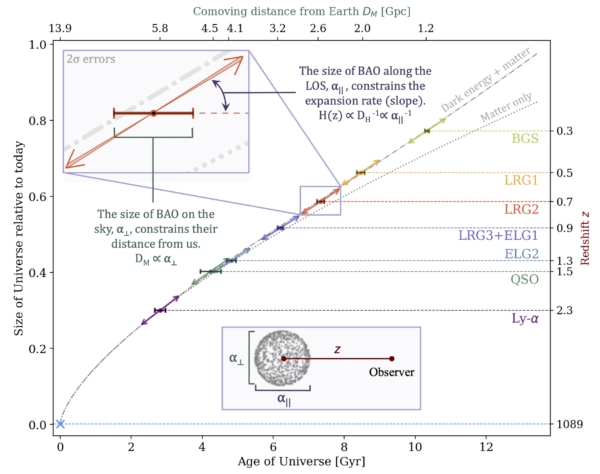

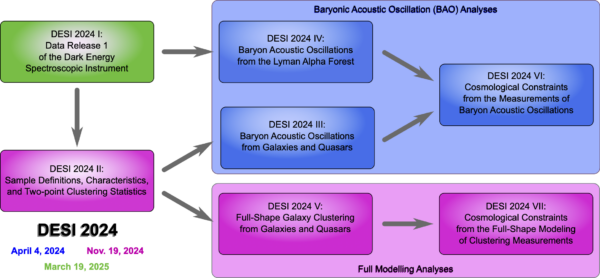

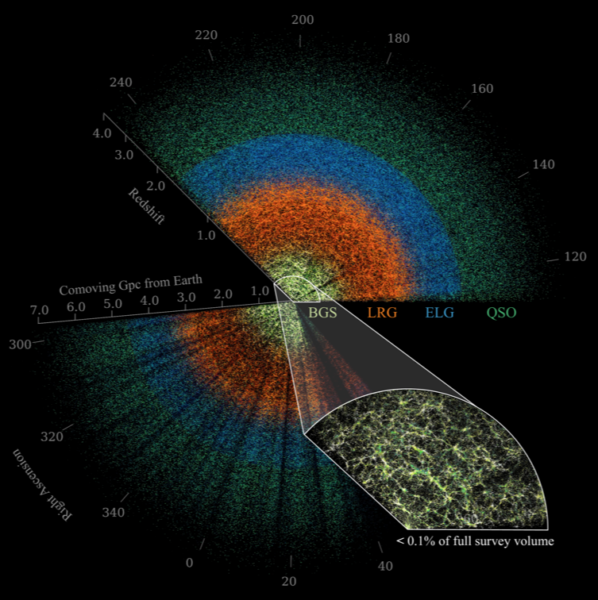

In the next few months, the DESI High team will be finalizing updates to the repository. Besides updating the current Jupyter notebooks to work with data from the DESI’s first data release (public as of 19 March), we will also introduce some new notebooks. One will feature a shorter but more straightforward introduction to Dark Energy and DESI. Another one will illustrate how we measure distances in cosmology. And a third will introduce Baryon Acoustic Oscillations! With these visually interesting, step-by-step Jupyter notebooks, we look forward to many future events that use the DESI High tutorials to spread the excitement of cosmology and DESI discoveries!

— edited by Joan Najita

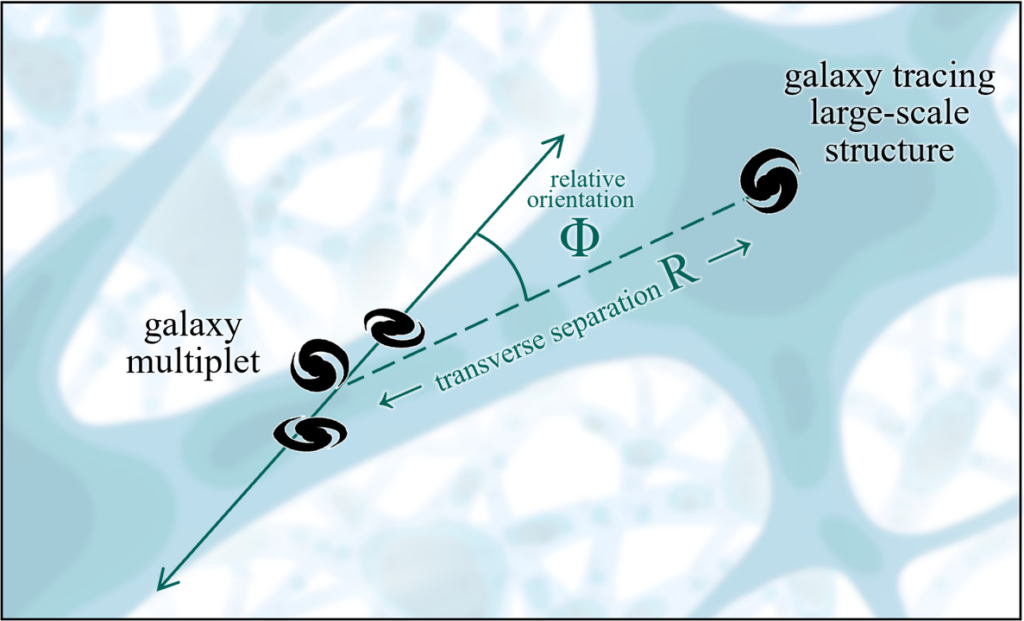

A graduate student at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Claire Lamman studies the orientations and alignments of galaxies and what they can tell us about cosmology and the cosmic web. She is also a talented artist and the recipient of a National Academies of Sciences

A graduate student at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Claire Lamman studies the orientations and alignments of galaxies and what they can tell us about cosmology and the cosmic web. She is also a talented artist and the recipient of a National Academies of Sciences